A screenshot from ‘Flower’ (2009)

In Karl Marx’s text The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte he outlines his basic description of agency: ‘Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.’ This essential dialectic also frames a core Marxist concept of ideology under capitalism. In the modern, late capitalist era, our current economic system faces an existential ecological crisis, again providing an impetus to explore other conceptions of organisation of economy and ideology that stem from that wider set of ‘circumstances’ Marx outlined.

This essay will explore some of these economical-ideological related questions coupled with the context of ecological crisis and radical conceptions of agency, in relation to the independently developed game Flower (2009), utilising ideas from Marx, Marxists artists, as well as other game designers.

In Flower the player takes control of a mysterious gust of wind, drawn toward the petals of many flowers across a field. As the game continues the player take these petals on a journey, accumulating and collating them in greater numbers, soaring across wider gusts of wind to the next destination.

The game’s first level only showcases the wilderness and impressive and artful rendering of pastoral environments in digital form. In the game’s second level we begin to see the wind bringing back colour and changing the environment. It was this minimalist design with a meditative tone that Flower that was primarily known for in press and media.

However it is in the third level that the player may notice the subtle emergence of human existence, in the form of wind turbines. This complicates the level design experience allowing for fast currents of winds. In the fourth level a night time environment is lit by human power-lines and lampposts, and the first ingame ‘threat’ in the form of menacing pylons, appears. If the player hits these they take damage, losing petals. In the next level these threats begin to mass and start to reach for the player, who will need to adeptly avoid them to progress. The fifth level ends in a moment of defeat by the wind, surrounded in a sea of pylons of which there is no escape.

Here a narrative progression has moved the player from the start, a harmonious dreamlike natural world, increasingly into a more urban and threatening environment. This process culminates in the game’s largest final level, the city.

Concept Art from ‘Flower’ (2009) showcasing the duality between nature’s purity and toxic capitalist modernity.

It is at the city where the player is given the most ample opportunity to change the content of the level. The city is a more open/sandbox environment in terms of level design and what directions are available to the player. As the player accumulates more petals they return colour to the monochrome urban spaces of the city and somehow (perhaps with the collective strength of many petals) throttle the remaining pylons out of existence. Whilst this moment is physically impossible, the fantastical suspension of disbelief offers the player a triumphant and poetic narrative, of the meek and many triumphing over the strong and monolithic.

It is in Marx’s prescient writings on ecology here that we find a direct connection with Flower’s attack on the extremist dichotomy of urbanity and rurality. John Bellamy Foster’s summary of Marx’s concept of metabolic rift states: ‘’the concept of a rift… between human beings within capitalist society from the natural conditions that formed the basis for their existence. One way in which this manifested itself was in the extreme separation of town and country under capitalism, which grew out of the separation of the mass of the population from the soil.’ (Foster, 2019). It was central part of Marx’s wider political programme, and the economic ideology of communism, to seek a democratic form of self-management, based in the working-class, through communes that could decentralise and dissolve the contradiction between town and country.

Alexander Lehner describes the final level in Flower as follows ‘… in the sixth level, there is hope for the cooperative work of the human and the non-human. Rather than destroying the cultural effects within the environment, they are transformed into something cooperating with nature… Humankind is no longer depicted as an alien element in the former pure nature, but strives for synthesis with the non-human.’ (Lehner, 2019)

There is clearly an intended notion of profound ecological purpose, and perhaps an unintentional radicalism, in a game in which the encroaching world of capitalist modernity is reclaimed by nature, replacing it not with total destruction and sublimation to rurality but of a synthesis. Yet to find further radical or Marxist conceptions within Flower’s ecology it is necessary to consider two core elements of the game: aesthetics and agency.

There are many politically radical aspects of Flower‘s final scene. The aesthetics of the ending in which the protagonist (wind and petals) smashes away the decaying pylons, transforming the world into colour, in an epic ideological battle of abstract shapes appears unconsciously reminiscent of the some of the art of the Constructivist movement, an art movement in early revolutionary Russia. Particularly Lissitzky’s iconic ‘Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge’ (1919)

‘Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge’ – (1919) a Soviet propaganda poster by Lazar Markovich Lissitzky

The metaphorical aesthetics of this image and in Flower broadly is of collective agency embodied in a fictional holistic avatar. This points to the wider political radicalism within Flower, through not just visual depictions but its complex and unconventional nature of play, specifically through agency. In Flower it is worth considering – is the player controlling a manifestation of an abstract dream or a more organic historical process? Is the player the wind, or the petals they accumulate? The text itself suggests the answer would be appear to be an amalgamation of all possibilities and thus the text’s only answer to such questions is: …Yes. This furthers a greater need for consideration of the complexities within the game’s design and themes with a wider application of existing theories on agency.

Sergei Eisenstein became a popular Marxist film director in Russia during the same era as the Constructivists. Eisenstein has latterly become associated with a crude reductionist approach to his concepts of ‘collective narrative.’ Often cited as the Ur-Marxist film maker, it is often suggested that his film’s collective narrative could be simplistically contrasted with western (Hollywood) cinema. The dichotomy is framed with individual character-focalised narratives of the west and no individual narrative in the east. In fact when discussing his ‘mass films’ Eisenstein stated that ‘collectivism means the maximum development of the individual within the collective, a conception irreconcilably opposed to bourgeois individualism.’

Sergei Eisenstein’s ‘Battleship Potemkin’ (1925) utilises a hybrid of collective and individually focalised narratives

This is directly comparable with the agency of the player in Flower whom is focalised around a single entity ‘the gust of wind’ that is also itself an embodiment of the petals which it accumulates. A clear political comparison can be made here. While in Flower the wind provides energy (much a like a historical current) it is only the participation of the petals (much like the masses in uprisings) that the wind has any power. This itself echoes much of the famous, if imperfect, quotation from the Marxist revolutionary Leon Trotsky: ‘Without a guiding organisation, the energy of the masses would dissipate like steam not enclosed in a piston-box. But nevertheless what moves things is not the piston or the box, but the steam.’ (Trotsky and Eastman, 1930)

In Flower the game is clearly exploring the idea of a typical western narrative, with a hero, and opposing force, and a changed world as the resulting product of the dénouement. Yet as a text, the game does not dwell in providing coherent or consistent understandings of the plot. Remaining free of any dialogue the game keeps one foot seated deeply in the tradition of an abstract narrative.

Additionally, the ‘epic’ and revolutionary narrative emerges slowly and surprisingly from the text itself. This ‘surprise’ of the arrival of the masses on the front of history during times of social upheaval is an extremely commonly cited historical/cultural concept. Flower offers us a surprise, in which the smallest and meekest can make the biggest changes. The game never promises such a narrative but slowly delivers it to us against our own suspicions and expectations. Within this role individuality remains consistent, the player focalises around the growing thrust of events, the literal wind of change, who itself is attached to a wider network and nebula of identity around its acquired team mates, the petals.

There are other comparable games wherein the player character/avatar is a ‘mass’ of characters with a shared collective goal. The Wonderful 101 (2013) focalises the player around the agency of a team of up to 101 different super heroes who stand in a crowd together. This is directly satirised/détourned in Anarcute (2016) with a similar urban environment but with the twist of ‘kawaii’ anthropomorphic characters taking on an oppressive government through rioting.

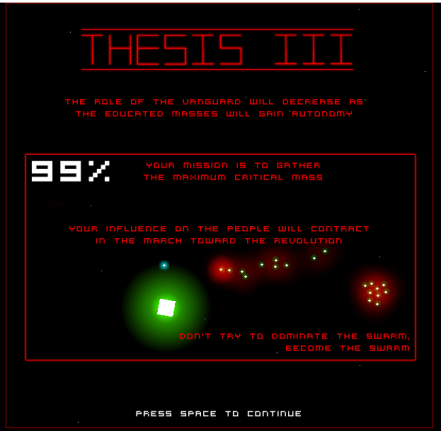

The challenges of these experiences is often in holding the masses together. The ideological apotheosis of this concept of design can be found in Kosmosis a 2008 game that plays similarly to Flower mechanically and fully embraces the collective narrative and metaphor of shared agency to a collectivist movement. It begins with a series of ‘thesis’ explaining the multi-layered metaphorical approach to playing as a vanguard entity, that will not always be in control of the action and will, over time, become less and less relevant, as the game plays itself.

A triptych showing the instructions (or ‘Thesis I-III’) for playing ‘Kosmosis’ (2008)

It is of note that whilst Flower was unique for a mainstream release in 2009 to explore these ideas, it clearly did not view its collective mechanic as its unique selling points of innovation in the way Kosmosis does. In much the same way the wider political texture of Flower seems implied, open to interpretation and implicit. This may be precisely why academics have taken interest in the political implications of Flower. Perhaps most notably the article of the South African Journal of Philosophy (du Plessis, 2018) that explores the works of Giles Deleuze in the context of Flower both a sense of “becoming-other” as well as the violent accumulation of power. These arguments take a different theoretical work as a basis for their analysis and yet still tilt to similar conclusions regarding the sense that Flower embodies a ludological exploration and engagement with radical ideas around collective change, amidst ecological dissonance, crisis and looming retransformation. The concept of violence appears to exist predominantly in the ‘forceful’ nature of the gust of wing. All political mass movements have debated the concepts, regretfulness, or inevitability of applications of violence. So the application to a game like Flower may seem odd, yet the forceful nature of change it depicts could be considered by some to be an elitist conception of a heroic minority rescuing the world, much in a typical Hollywood western narrative.

None of the arguments of this essay are to apply a didactic implication of suggested closet communistic sympathy within Thatgamecompany, but to consider the economically driven ideological concepts specific to culture with an ecological focus. In Flower there more than mere echoes of the ideas of capitalism vs communism, or of modernity vs ecology. Instead we find a metaphorical discourse over the agency of an imagined ‘masses’, with a goal (or destiny) in search of radical shifts and change toward a greater symbiance between nature and urbanity. In Flower the intended message is for a reclaiming of modernity in the face of ecological failure. This is in and of itself presents greater questions and dichotomies. Flower as an interactive experience should thus be considered as a prescient and radical starting point to the unfinished dialectic of the present.

Bibliography

Ludography

Molleindustria 2008, Kosmosis, online game, [Accessed via] http://www.molleindustria.org/kosmosis/kosmosis.html [On 02/04/19]

Thatgamecompany 2009, Flower, digital game, Playstation 3, Sony, USA

PlatinumGames 2013, The Wonderful 101, digital game, Wii U, Nintendo, Japan

Anarteam 2016, Anarcute, digital game, PC (Steam)

References

MARX, K., & DE LEON, D. (1898). The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. New York, International Pub. Co. http://find.galegroup.com/openurl/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_ctx_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&res_id=info:sid/gale:MOME&ctx_enc=info:ofi:enc:UTF-8&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:unknown&rft.artnum=U113081119&req_dat=info:sid/gale:ugnid.

Capitalism and ecology: The nature of the contradiction John Bellamy Foster. Monthly Review; New York Vol. 54, Iss. 4, (Sep 2002): 6-16. https://search.proquest.com/openview/bf4ab66fd00ec406866b02bd95ca4ec0/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=48155

Lehner, A. (2019). Videogames as Cultural Ecology: Flower and Shadow of the Colossus // Videojuegos como ecología cultural: Flower y Shadow of the Colossus. [online] Ecozona.eu. Available at: http://ecozona.eu/article/view/1349/2089 [Accessed 02 Apr. 2019].

Jsiming.com. (2019). [online] Available at: http://www.jsiming.com/portfolio/print_design/ElLIssitzky_magazineDesign_spreads_07Jul25.pdf [Accessed 2 Apr. 2019].

Eisenstein, S. and Leyda, J. (1968). Film form. New York: World Publishing.

Trotsky, L. and Eastman, M. (1930). History of the Russian Revolution.

du Plessis, C. (2018). Subverting utilitarian subject-object relations in video games: A philosophical analysis of Thatgamecompany’s Journey. South African Journal of Philosophy, 37(4), pp.466-479.